![]()

Class 3

User Interface, continued

Review

In Class 2 we learned that a pointing device is usually an electro-mechanical device that converts the action of our REAL pointing device (our pointing finger) into signals that the computer can understand. While touch screens can actually respond to the touch (not poke!) of a finger, not all computers have touch screens.

If you have NOT worked your way through Class 2, please do so now!

A mouse is currently the most used pointing device. The mouse simulates your touching an object on the screen by sensing your pointing finger pressing (clicking) a switch. It also allows you to move an object on the screen the way you would move a 'checker' on a 'checker board'.

- You put a finger on the checker (point to the object on the screen with your pointing device cursor, click and HOLD the button under your index finger)

- - slide the checker to the new location (move the mouse while holding your index finger DOWN on the mouse button until the cursor AND object on the screen are in the correct location)

- - STOP MOVING THE MOUSE!

- - then take your finger off the checker (remove your index finger from the mouse button).

There are numerous ways to start an application. We started the Control Panel and using the Mouse app-let (little application) we modified some of the behaviors of our mouse pointing device.

An application like Solitaire, a game application, is probably the most comfortable way to learn the hand motions required when using a Mouse. It is also a recommended hand-eye coordination exercise.

The Class Synopsis follows this paragraph. You should notice that individual sections of this class are colored and underlined, indicating that they are LINKS to the appropriate sections. You may click or touch individual sections to jump to them, or simply scroll down (turn the mouse wheel, if it has one) to the section you wish to continue with.

1) Cursor Shape Change

![]()

We humans have learned to read meaning into things that change color (traffic signal: Red, Amber, Green) and traffic signs that have different shapes (Hexagon = Stop, Triangle = Slow Moving Vehicle, Circle = No Entry, Dead End, etc). Now we have an opportunity to observe our computer cursor which can change shape depending on where it is; giving us a clue as to an alternate action we can invoke, usually by ‘clicking’ the pointing device button (or doing a drag and drop action) while the cursor has its new shape.

Because the shape change is part of the user interface, we need to know what we can do when the cursor changes shape. Fortunately, the shape it changes to pretty much tells us what we can do with it. The following list of different cursors (pointers) includes a description of its function. As we learn the user interface, we will learn what the descriptions mean. We actually will use many of them as we discuss the Properties of a Window in the next section.

![]() Normal Select

Normal Select

![]() Text Select (Basically, this one means you are in a text box!)

Text Select (Basically, this one means you are in a text box!)

![]() Precision Select

Precision Select

![]() Not Available

Not Available

![]() Link Select (When using the Internet)

Link Select (When using the Internet)

![]() Busy

Busy

![]() Horizontal Resize

Horizontal Resize

![]() Vertical Resize

Vertical Resize

![]() Diagonal Resize 1

Diagonal Resize 1

![]() Diagonal Resize 2

Diagonal Resize 2

![]() Move

Move

These are not the only changes you will see, but others also will show you what you can do.

2) Properties of a Window

![]()

All objects have properties. Computers are no exception. Every component of the device we call a personal computer has properties. This class is about the properties of a window.

Merriam-Webster defines Property as:

- (a): a quality or trait belonging and especially peculiar to an individual or thing (b): an effect that an object has on another object or on the senses (c): virtue (d): an attribute common to all members of a class

- something owned...

First use: 14th century

Example: the ability to be magnetized is a common property of iron...

Another term 700 years old. See! I told you that you know more about computers than you think you do.

Every time you start an application, a window is opened to focus your attention on the application. Everything you can do TO a window, can be done to EVERY window on the computer. They all work the same way.

Let us first consider the control you have over every window. These are the properties of a window. Any window can be made to fill the screen. If you need to get it out of the way, you can minimize it to an icon on the taskbar of your desktop. When you choose to keep it open on the desktop, but not fill the screen, you can change its size and shape as well as move it anywhere on the desktop you wish.

Ah-HAH! you say. “What happens when I have two or more windows open? How can I tell which one is the one I am working with?”

If both/all the windows are sized such that they overlap, the one you are working with is always ‘in front’ of the others. You can also choose to personalize the color of the title bar of any ‘active’ window, (the window you are currently working on).

Give your windows a bit of color

This is another personalization exercise for your computer (first was the mouse). Poke the Windows logo key on your keyboard, find the gear icon (settings) in the lower left area of the start screen and select it (Windows 11: find the gear icon among the other icons on the start screen).

When the settings window opens, find Personalization and select it. In the left column of the personalization window, find Colors and select it. Move your cursor to the right hand column. You should see a block of color squares. You may need to rotate the wheel on top of your mouse until you reveal the color blocks. Select one you like.

When you have made your selection; with your cursor still in the area of the window with the colored blocks; rotate the wheel on top of your mouse until you reveal some check boxes below the color blocks. Find the one to “show accent color” on the Title Bars and select the checkbox to put a check mark in it. Close any open windows by moving your cursor to the top right corner of the window, an area with an X that will turn red WHEN YOUR CURSOR IS NEAR THE X. Select it to close the window.

Title Bar

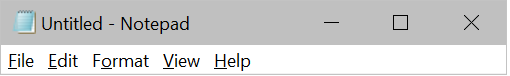

We are going to open an extremely simple window to examine some of the windows properties. Poke the Windows logo key on your keyboard, and BEGIN to type notepad. After you type each character, check the screen to see if notepad popped up. When you see it STOP TYPING. Select the name notepad. This will open a window for the app Notepad.

The notepad window should not fill the entire screen. If it does, move your cursor to the top right area of the window, locate the double square icon left of the X used to close a window. Select the double square icon (view multiple windows icon) to take the window out of full screen mode.

Now for the first cursor shape change. At ANY edge or corner of the window, the shape of your cursor will change to a resize cursor!

Move your cursor to the bottom edge of the window. As you move the cursor across the edge, the cursor should change to the vertical resize shape. Stop moving the mouse when you see the cursor change. Then do a drag and drop action, moving the bottom edge as close to the top of the window as it will go. NOTE: Windows 11 will not allow you to make a window that small. Refer, instead, to the photo below.

You should now be looking at the so important Title Bar.

![]()

A Microsoft Windows 10 title bar is shown. Other operating systems may display the information in a different order. ALL (most) title bars have the following information:

● The Title of the application (That is why it called the Title Bar!)

● An Icon representing the application

● The Name of the file opened, if the file has been given a name

● An Icon of a dash or underscore character

● An Icon of one or more squares (view one or more windows)

● An Icon of an X (close the window you are looking at)

When a window does NOT fill the screen, you can move the window to any area on your desktop that you choose. Position your cursor somewhere on the title bar that is NOT on an icon. Do a drag and drop action to move the whole window.

Note: the title bar is the ONLY part of a window that will allow you to move the window.

Move your cursor to the dash or underscore icon, and pause. If you don’t move the cursor for a few seconds, the computer will pop up a brief description of what the icon is for. The dash or underscore icon, when selected, will minimize the window to an icon (the same icon that represents the application) on the taskbar where you can find it to restore the window to the desktop, in its original size and position.

Move your cursor to the single square (view window full screen) or multiple square (restore window to original size and position) icon, and pause. If the icon is a single square, select it to make the window fill the screen. If the icon shows multiple squares, select it to restore the window to the desktop in its original size and position.

Move your cursor to the X and pause. The first thing you will notice is, the area around the X turns bright RED! Like a red traffic signal, this is a warning! If you select the X, the window will be CLOSED. Any unsaved work you were doing will be gone. Most windows will remind you to save your work. You will have to start the application again if you want to work with it some more.

![]()

Menu Bar

The next property of a window is a Menu bar. Move your cursor to the bottom edge of the title bar and watch for the cursor to change back to the vertical resize cursor. Stop moving the mouse when you see the cursor change. Then do a drag and drop action, moving the bottom edge down until it reveals the menu bar. NOTE: Windows 11 will not allow you to make a window that small. Refer, instead, to the photo below.

This form of the menu bar is still used in many applications. Having a menu is a property of a window, but what appears in the menu bar is under control of the application. Most menus will have a File menu and a Help menu. When you select a menu, a pop up or pull down list will appear, which lets you modify the operation of the application. For instance: most File menus will let you Open, Save, Close files, and Print pages the app is generating for you.

If you have questions about how to use the application, check the Help menu first!

Status Bar

Windows 11 limits the smallest size of a window to the size discussed in this paragraph. Windows 10 users: Once again, move your cursor to the bottom edge of the open window and watch for the cursor to change back to the vertical resize cursor. Stop moving the mouse when you see the cursor change. Then do a drag and drop action, moving the bottom edge down until it reveals some blank space between the menu bar and the bottom edge of the window (and, possibly, the Status bar).

NOTE: All of the blank space (in this case) between the menu bar and the status bar (or the bottom of the window) is called the Application Workspace, discussed below.

As of this writing, the most recent Windows 10 update hides the status bar in the Notepad application, when there is no status to report. Move your cursor to the ‘View’ choice in the menu bar. The ‘drop down’ menu should include ‘status bar’; therefore, to ‘view’ the ‘status bar’, click on ‘status bar’!

Notepad is not the only application that is capable of hiding or unhiding the status bar. Look for that action in the menus, probably under the View menu because it changes how you view the application window.

The status bar is there to inform you of anything you need to know while working with the application. For instance, an application may require that you place three points. The status bar would tell you to place point 1, after you place it the status bar would tell you to place point 2, etc.

You are now done with the ‘Notepad’ exercise. You may close it if it is still open.

Application Workspace

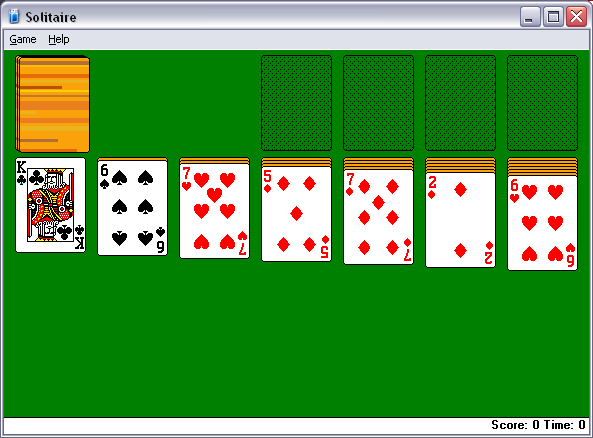

The window that opens when you start an application provides a workspace for the application, so everything in the workspace is controlled by the application. EVERYTHING between the Menu bar and the Status bar is considered the application workspace. Check the handout of an old version of Solitaire.

The entire application workspace in this version of Solitaire is green, to simulate a card table surface. Notice also, the status bar is keeping track of Score and Time.

Tool Bars

Consider a room in your home, such as your garage. Some people choose to use it to house their vehicle. The garage, therefore, would usually have tools to change oil, wash the car, maybe change a tire, etc. Someone else may choose to use the garage for a wood shop. The tool set changes to saws, planers, hammers, maybe carving tools, etc. Yet another home may have set the garage up for gardening, so it would have lawn mowers, perhaps a riding lawn tractor, shovels, hoses, etc.

Similarly, on a computer, when an application opens a window, it will provide its own tools; the tools that are appropriate for the application.

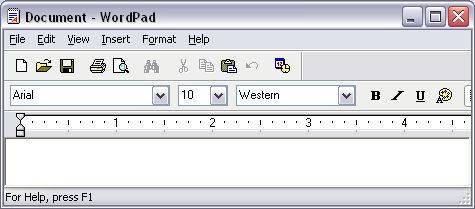

Tool bars were added to applications to simplify application controls. Instead of having to open menus to find tools, they were put in tool bars to make them more instantly visible. The tool bars are a part of the application workspace (positioned between the menu bar and the status bar) and change by application. The icons used, however, have become sort of standardized. Many similar apps will use similar icons for the same kind of function. The next photo is a early version of WordPad.

In this illustration, under the menu bar, you see a tool bar with icons that have the same functions as the File menu.

The next tool bar down, similar to the Edit menu, has text boxes to change the font type, font size, font style, as well as icons to make text bold, italic, underlined and change its color, etc.

Then, there is a ruler showing the width of the ‘paper’ with tab positions, etc.

Notice, also, the status bar is giving the user some helpful information.

Tool bars were so successful, that a newer version of tool bars is called a ribbon. With it came a change from pull down menus to tabbed menus. A tab is nothing more than pretending you are looking at a full file drawer and checking for what you want by looking at the numerous tabs sticking out of the mass of folders and papers. With a file drawer, you grab the tab and pull the file folder you want out of the drawer for use. In a computer tabbed menu, you select the tab you want and the folder contents (in the form of tools clustered by category) is opened for you!

The new tabbed menus and ribbons require much higher screen resolution than the older versions of a window I have been demonstrating above. They can best be viewed on a real computer. By now you should know how to open an application, so open the application WordPad. Compare the window that opens with the WordPad window above.

Ribbons take more space from the application workspace, but they can be temporarily removed from view. Check out the small up arrow at the far right of the new WordPad menu bar. Selecting the arrow removes the ribbon from view. It also turns the arrow around, so selecting it again, will restore the ribbon.

3) Scroll Bars

![]()

In order to test the scroll bars, we will use our Paint application. Open the application Paint. Make sure the Paint window is NOT full screen. In fact, make it about 1/4 screen size.

We are going to perform an action commonly called a screen grab to capture a ‘photo’ of the entire desktop. Find the Print Screen (PrtScr) button on the keyboard and poke it. (May need a Function (Fn) key as well on a laptop!) A photo of the full screen has now been copied to the computer's clipboard. The clipboard holds only one item, and is invisible. You can only see what is on the clipboard by doing a paste operation.

Anytime you do a copy and paste, or cut and paste operation, you are also using the clipboard.

Make sure your Paint app window is selected (if you set up personalization to color the title bar of a window (above), your paint title bar should have that color when selected), and 'paste', either via the Paste icon just under the word File in the menu bar, or the keyboard shortcut CTRL-V. You should now have scroll bars at the right edge of the Paint window (you can only see 1/4 of the screen at a time).

Scroll bars appear in a window when there is too much information in the application workspace to view with the current size of the window. If there is too much information in the horizontal direction, the scroll bar will appear at the bottom of the window just above the status bar. If there is too much information in the vertical direction, the scroll bar will appear at the right side of the window.

There are up to five active areas in a scroll bar. We are going to consider the horizontal scroll bar just above the status bar in your Paint window. If you have sized your Paint window as suggested above, the first thing you should notice about the scroll bar is a white area, and a greyed out area. Position your cursor on the greyed out area, and do a drag and drop action to move the grey area to be centered in the scroll bar.

You can now see all five active areas of a scroll bar: an arrow head at either end of the scroll bar (using Windows 11, you will only see the arrow heads when you move your cursor into the scroll bar!), the grey bar you have moved to the center of the scroll bar (which slides as you move it to any position on the scroll bar. A slider, if you please.), and two white areas between either side of the grey bar and the arrow heads at either end of the scroll bar. EACH OF THE FIVE AREAS WILL DO SOMETHING FOR YOU!

The first and most used area is the grey area usually called a slider. You already know you can do a drag and drop action on it to move the information in the application workspace left and right. In the case of the vertical scroll bar at the right side of the window, it would move the information in the application workspace up and down.

The next two areas are the arrow heads at either end. A click on either one will cause the slider to jump a discrete amount in the direction the arrow is pointing. Please click on each arrow head to see what they do!

The remaining two areas may or may not be present. Depends on the width of the window and the amount of information. A click in either area will cause the slider to jump the same distance as the length of the slider. Again, please click in appropriate areas to see what they do.

The last thing I want you to experience is how the scroll bars depend on the size of the window, and on the amount of information in the application workspace. If you look closely at the bottom right corner of the Paint window, you will see that the corner has a number of dots filling the corner (Windows 11 does NOT have the dots). Position your cursor as carefully as you can in the corner. You will know you are in the corner if your cursor takes on the shape of the diagonal double headed resize arrow. Press you pointing finger down and hold it while you move your pointing device about, and watch the size of the scroll bar sliders change accordingly. In our case, you cannot move the corner to make the window large enough to make the scroll bars disappear because the image in the Paint window is the size of your full screen.

Remembering that the ‘Photo’ in Paint is a photo of the full screen, and that it includes photos of title bars, locate the REAL title bar, the one that will MOVE the Paint window. Once you have found it, carefully look just below the title bar to find a menu bar. One of the selections is View. If you choose View, you will see zoom icons (except in Windows 11). You can change the size of the information to eliminate or restore the scroll bars. There is also a zoom slider at the bottom right of the Paint window in the status bar, with + and - buttons you can click on.

When you are done exploring scroll bars, close the Paint window.

4) Dialog boxes

![]()

Humans understand that a dialog is a two way conversation usually used to resolve a problem. In our case, the dialog box is the computers way to ask for specific information, and frequently will not allow you to go on without answering the question.

The computer dialog box looks like a typical window, with differences. The title bar will still allow you to move the box, but if you examine the title bar closely, you may not see the X used to close a window. Even if you do have the X, you will NOT have the icons to minimize or resize the window.

Most of the items on the Control Panel are presented to you to allow you to change computer behavior of the item you select. As such, a click on any item will open a dialog box, rather than a window. You then get to choose a behavior and make appropriate changes.

The most popular means you will be presented with to make desired changes are: sliders, check boxes, radio buttons and text boxes.

Open the Control Panel now to view the changeable items. For this exercise, choose the Mouse item. The mouse dialog box uses a tab style menu where a normal window menu bar would be. Appropriate tabs are called out below:

Sliders >> Buttons tab: You already know how to use sliders from the section on scroll bars, and the specialized zoom slider on the status bar of some applications. Dialog box sliders look like the zoom slider. You can either drag and drop the slider to make your choice, or you can click directly on the bar the slider moves on to reposition it.

Check box >> Pointer Options tab: Most humans have already used check marks to indicate their choices on their own personal lists. A computer check box is not much different. There is a box for the check mark, and a description of what a check in the box will do. You may click the box itself, or the description next to it to make or remove a check mark.

Radio buttons >> Wheel tab: A radio button is a specialized check box. Actually, it is a circle, not a box, so you know what to expect. In any given collection of choices, only one will allow being selected at a time, just like the old automobile and console radios. The user programmed the button to tune a specific radio station. You could then rapidly tune you favorite station just by pushing a button. That action would cancel the old station and tune to the new station.

In the ‘Vertical Scrolling’ area of the Wheel tab, you will find a very small collection of Radio Buttons (2). Try to select both of them. Notice it won’t work. That is the best feature about radio buttons. Only one button in a group can be active.

Text box >> Wheel tab: A text box typically is just an empty white rectangle. You click IN the box before you can begin typing your text.

The Wheel tab has a text box with up and down arrows at the right end of the box. You may click on the arrows to increase or decrease the value in the text box, or you may highlight (swipe text to select) the value and type in a new one.

The Pointers tab has yet another text box, one with a single arrow head at the right end. This is a pop up or drop down text box. A default value is displayed in the box. Click in the box to change the value and it will pop up or drop down all the possible options. Select your choice. If you approve the choice, click the button marked Save As to keep it.

You may have noticed three buttons at the bottom of the dialog box: Apply, Cancel and OK. Apply means “Computer, make the change(s) I have selected, I am going to look at a few more.” Cancel means “Oops, I didn’t mean that, lets get out of here!”. OK means “Ok, I am done. Make any changes I’ve made and close the dialog box.”.

Close the dialog box (you can use the X), the exercise is done.

There are some other ways you can exercise a choice in a dialog box, but these are the major ones. As programmers get different ideas for creating a dialog between you and your computer, you can bet you will see changes.